To CHAT with us, click the bubble at the bottom of your screen.

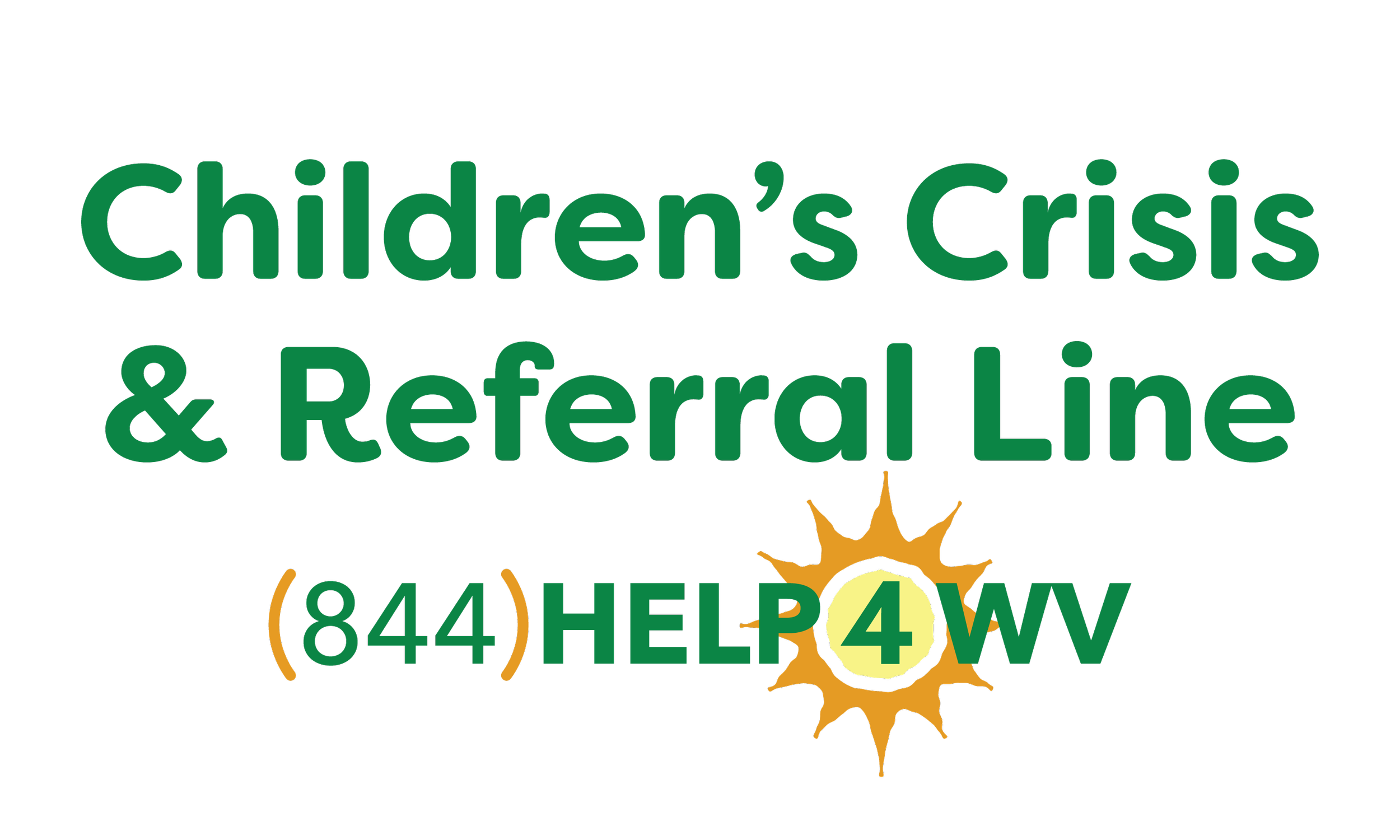

When it comes to children, it may be easy to see that something is wrong, yet scary and challenging to know where to find help. The Children’s Crisis & Referral Line is available 24/7 to assist in finding the most appropriate available treatment for youth behavioral health needs. We can provide parenting support, crisis counseling, and local resources for your family.

Our goal is to offer support that facilitates children staying in their homes, schools, and communities. We can provide information on a wide array of services and resources for children relating to:

Mental health disorders

Behavior concerns

Substance use

Intellectual and developmental delays

Emotional wellbeing

Resources

4

Your

Family

The resources we refer to include:

WEST VIRGINIA WRAPAROUND

A wraparound facilitator builds a team of community partners and supportive family and friends to develop a plan that will help support the family and child to keep the child thriving at home.

CHILDREN’S MOBILE CRISIS RESPONSE AND STABILIZATION TEAMS

A small team provides immediate assistance over the phone or is available to come quickly to de-escalate a crisis.

POSITIVE BEHAVIOR SUPPORT

Services range from a one-hour telehealth brainstorming session, to a youth-centered plan for behavior improvement, to intense in-home services.

REGIONAL YOUTH SERVICE CENTERS

These professionals focus on early detection, treatment, and recovery for young people experiencing addiction or mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and psychosis. The services are provided on an outpatient basis with a goal of helping the youth thrive in their own home.

REGIONAL YOUTH TRANSITION NAVIGATORS

This program connects youths and young adults aged 14-25 who have trouble functioning due to a mental illness or addiction, with support to develop independent living and people skills, navigate systems like health care and education, and access and participate in treatment and recovery services.

COMPREHENSIVE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CENTERS

These regional centers provide a continuum of mental health services, including psychiatric assessment and outpatient counseling.

parentguidance.org

The West Virginia Department of Education has made this resource available to families, educators, caregivers, and others to support student mental health. It is a 24/7 online platform that provides parenting coaching, courses, and a forum to ask questions of a professional therapist.

Talk to someone who cares. Life can present unanticipated challenges and stress. Whether you are overwhelmed by demands of school or work, feeling lonely or discouraged, or just need to vent, we are here to listen without judgment, and to offer resources, tips and support. Contact 844-HELP4WV now to talk to someone who cares.

Although we encourage you to call us to find the treatment that best fits your family, you may want to explore options on your own. West Virginia has many resources for families who need mental health support:

If your child appears to be experiencing psychosis, the Quiet Minds program can help.

If you are concerned your child may be suicidal, learn more here. You can also call the Suicide Lifeline 24/7 at 988.

If your child or any member of your family needs assistance with addiction, we have over 1,000 resources to assist with that. Our helpline specialists can immediately connect you to many different types of treatment. Call 1-844-HELP4WV.

The WV 211 program has thousands of resources to help you take care of your family’s immediate life-sustaining needs. If you need information on any type of social service, including food pantries, housing assistance, or utility assistance, this program can be reached 24/7 by dialing 211.

If you are a victim of domestic violence, the WV Coalition Against Domestic Violence can help. You can also call 1-800-799-SAFE.

If you think your child may have an intellectual or developmental disability, you can find help here.

Learn more about behavioral health services available for West Virginia children here.

Funding provided by the WV Department of Health and Human Resources, Bureau for Behavioral Health with a federal grant from SAMHSA.

Common Behavioral Disorders in Children

Concerned your child may be suffering from a mental illness or behavioral disorder? The following information from the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry describes some of the most commonly diagnosed childhood disorders.

-

All children experience some anxiety. Anxiety in children is expected and normal at specific times in development. For example, from approximately age 8 months through the preschool years, healthy youngsters may show intense distress (anxiety) at times of separation from their parents or other people with whom they are close. Young children may have short-lived fears, such as fear of the dark, storms, animals, or a fear of strangers.

Anxious children are often overly tense or uptight. Some may seek a lot of reassurance, and their worries may interfere with activities. Parents should not dismiss their child's fears. Because anxious children may also be quiet, compliant, and eager to please, their difficulties may be missed. Parents should be alert to the signs of severe anxiety so they can intervene early to prevent complications.

There are quite a few different types of anxiety in children.

Symptoms of separation anxiety include:

Constant thoughts and intense fears about the safety of parents and caretakers

Refusing to go to school

Frequent stomachaches and other physical complaints

Extreme worries about sleeping away from home

Being overly clingy

Panic or tantrums at times of separation from parents

Trouble sleeping or nightmares

Symptoms of phobia include:

Extreme fear about a specific thing or situation (ex. dogs, insects, or needles)

Fears causing significant distress and interfering with usual activities

Symptoms of social anxiety include:

Fears of meeting or talking to people

Avoidance of social situations

Few friends outside the family

Other symptoms of anxious children include:

Many worries about things before they happen

Constant worries or concerns about family, school, friends, or activities

Repetitive, unwanted thoughts (obsessions) or actions (compulsions)

Fears of embarrassment or making mistakes

Low self-esteem and lack of self-confidence

Severe anxiety problems in children can be treated. Early treatment can prevent future difficulties, such as loss of friendships, failure to reach social and academic potential, and feelings of low self-esteem. Treatments may include a combination of the following: individual psychotherapy, family therapy, medications, behavioral treatments, and consultation to the school.

If anxieties become severe and begin to interfere with the child's usual activities (for example separating from parents, attending school, and making friends), parents should consider seeking an evaluation from a qualified mental health professional or a child and adolescent psychiatrist.

-

Many children have times when they are sad or down. Occasional sadness is a normal part of growing up. However, if children are sad, irritable, or no longer enjoy things, and this occurs day after day, it may be a sign that they are suffering from major depressive disorder, commonly known as depression. Some people think that only adults become depressed. In fact, children and adolescents can experience depression, and studies show that it is on the rise. More than one in seven teens experience depression each year.Common symptoms of depression in children and adolescents include:

Feeling or appearing depressed, sad, tearful, or irritable

Not enjoying things as much as they used to

Spending less time with friends or in after school activities

Changes in appetite and/or weight

Sleeping more or less than usual

Feeling tired or having less energy

Feeling like everything is their fault or they are not good at anything

Having more trouble concentrating

Caring less about school or not doing as well in school

Having thoughts of suicide or wanting to die

Children also may have more physical complaints, such as frequent headaches or stomach aches. Depressed adolescents may use alcohol or other drugs as a way of trying to feel better.

We don't always know the cause of depression. Sometimes it seems to come out of nowhere. Other times, it happens when children are under stress or after losing someone close to them. Bullying and spending a lot of time using social media may be associated with depression. Depression can run in families. Having another condition such as attentional problems, learning issues, conduct or anxiety disorders also puts children at higher risk for depression.

Sometimes parents are not sure if their child is depressed. If you suspect your child has depression, try asking them how they are feeling and if there is anything bothering them. When asked directly, some children will say that are unhappy or sad, while others will say they want to hurt themselves, be dead, or even that they want to kill themselves. These statements should be taken very seriously because depressed children and adolescents are at increased risk of self harm. Another way of identifying depression is through "screening" by your child's pediatrician, who may ask your child questions about their mood or ask them to fill out a brief survey.

If you think your child or teenager might be depressed, it is important to seek help. A pediatrician, school counselor, or qualified mental health professional can help by referring your child to someone who can conduct a comprehensive assessment, diagnose depression, and identify the right treatments.

-

The primary symptoms of ADHD are hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention.

Hyperactive children always seem to be in motion. A child who is hyperactive may move around touching or playing with whatever is around, or talk continually. During story time or school lessons, the child might squirm around, fidget, or get up and move around the room. Some children wiggle their feet or tap their fingers. A teenager or adult who is hyperactive may feel restless and need to stay busy all the time.

Impulsive children often blurt out comments without thinking first. They may often display their emotions without restraint. They may also fail to consider the consequences of their actions. Such children may find it hard to wait in line or take turns. Impulsive teenagers and adults tend to make choices that have a small immediate payoff rather than working toward larger delayed rewards.

Inattentive children may quickly get bored with an activity if it’s not something they really enjoy. Organizing and completing a task or learning something new is difficult for them. As students, they often forget to write down a school assignment or bring a book home. Completing homework can be huge challenge. At any age, an inattentive person may often be easily distracted, make careless mistakes, forget things, have trouble following instructions, or skip from one activity to another without finishing anything.

Some children with ADHD are mainly inattentive. They seldom act hyperactive or impulsive. An inattentive child with ADHD may sit quietly in class and appear to be working but is not really focusing on the assignment. Teachers and parents may easily overlook the problem.

Children with ADHD need support to help them pay attention, control their behavior, slow down, and feel better about themselves.

-

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) usually begins in adolescence or young adulthood and is seen in as many as 1 in 200 children and adolescents. OCD is characterized by recurrent intense obsessions and/or compulsions that cause severe discomfort and interfere with day-to-day functioning. Obsessions are recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses, or images that are unwanted and cause marked anxiety or distress. Frequently, they are unrealistic or irrational. They are not simply excessive worries about real-life problems or preoccupations. Compulsions are repetitive behaviors or rituals (like hand washing, keeping things in order, checking something over and over) or mental acts (like counting, repeating words silently, avoiding). In OCD, the obsessions or compulsions must cause significant anxiety or distress, or interfere with the child's normal routine, academic functioning, social activities, or relationships.

The obsessive thoughts may vary with the age of the child and may change over time. A younger child with OCD may have persistent thoughts that harm will occur to himself or a family member, for example, an intruder entering an unlocked door or window. The child may compulsively check all the doors and windows of his home after his parents are asleep in an attempt to relieve anxiety. The child may then fear that he may have accidentally unlocked a door or window while last checking and locking, and then must compulsively check over and over again.

An older child or a teenager with OCD may fear that he will become ill with germs, AIDS, or contaminated food. To cope with his/her feelings, a child may develop "rituals" (a behavior or activity that gets repeated). Sometimes the obsession and compulsion are linked; "I fear this bad thing will happen if I stop checking or hand washing, so I can't stop even if it doesn't make any sense."

Research shows that OCD is a brain disorder and tends to run in families, although this doesn't mean the child will definitely develop symptoms if a parent has the disorder. A child may also develop OCD with no previous family history.

Children and adolescents often feel shame and embarrassment about their OCD. Many fear it means they're crazy and are hesitant to talk about their thoughts and behaviors. Good communication between parents and children can increase understanding of the problem and help the parents appropriately support their child.

-

In children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), there is an ongoing pattern of uncooperative, defiant, and hostile behavior toward authority figures that seriously interferes with the child's day to day functioning.

Symptoms of ODD may include:

Frequent temper tantrums

Excessive arguing with adults

Often questioning rules

Active defiance and refusal to comply with adult requests and rules

Deliberate attempts to annoy or upset people

Blaming others for his or her mistakes or misbehavior

Often being touchy or easily annoyed by others

Frequent anger and resentment

Mean and hateful talking when upset

Spiteful attitude and revenge seeking

The symptoms are usually seen in multiple settings but may be more noticeable at home or at school. One to sixteen percent of all school-age children and adolescents have ODD. The causes of ODD are unknown, but many parents report that their child with ODD was more rigid and demanding than the child's siblings from an early age. Biological, psychological, and social factors may have a role.

-

Most infants and young children are very social creatures who need and want contact with others to thrive and grow. They smile, cuddle, laugh, and respond eagerly to games like "peek-a-boo" or hide-and-seek. Occasionally, however, a child does not interact in this expected manner. Instead, the child seems to exist in his or her own world, a place characterized by repetitive routines, odd and peculiar behaviors, problems in communication, and a total lack of social awareness or interest in others. These are characteristics of a developmental disorder called autism.

Autism is usually identified by the time a child is 30 months old. It is often discovered when parents become concerned that their child may be deaf, is not yet talking, talks in an unusual way, stopped talking, resists cuddling, and avoids interaction with others.

Some of the early signs and symptoms which suggest a young child may need further evaluation for autism include:

No smiling by six months of age

No back and forth sharing of sounds, smiles or facial expressions by nine months

Not responding when their name is called

No babbling, pointing, reaching or waving by 12 months

No single words by 16 months

No two-word phrases by 24 months

Regression in development

Any loss of speech, babbling, or social skills

A preschool age child with "classic" autism is generally withdrawn, aloof, and fails to respond to other people. Many of these children will not even make eye contact. They may also engage in odd or ritualistic behaviors like rocking, hand flapping, or an obsessive need to maintain order.

Many children with autism do not speak at all. Those who do may speak in rhyme, have echolalia (repeating a person's words like an echo), refer to themselves as a "he" or "she," or use peculiar language.

The severity of autism varies widely, from mild to severe. Some children are very bright and do well in school, although they have problems with school adjustment and peer interactions. They may be able to live independently when they grow up. Other children with autism function at a much lower level. Intellectual disability is commonly associated with autism.

Occasionally, a child with autism may display an extraordinary talent in art, music, or another specific area.

The cause of autism remains unknown, although current theories indicate a problem with the function or structure of the central nervous system. What we do know, however, is that parents do not cause autism, and childhood vaccines do not cause autism.

Children with autism need a comprehensive evaluation and specialized language services, behavioral, and educational programs. Some children with autism may also benefit from treatment with medication. Child and adolescent psychiatrists are trained to diagnose autism and to help families design and implement an appropriate treatment plan. They can also help families cope with the stress which may be associated with having a child with autism.

Although there is no cure for autism, appropriate specialized treatment provided early in life can have a positive impact on the child's development and produce an overall reduction in disruptive behaviors and symptoms.